Isabelle S.

20559660

I’m coming almost full-circle to completing a year of my life, blogged monthly within these posts. And within this context, I’m starting a new year, too. I’m starting again with school, and I’m starting again with new possibility. This is where I was back in 2013, when I first moved to Oregon - an incoming freshman going into a private liberal arts school, waiting to see what an education could or would bring, only with more desperation on the line.

I’ll be coming in with a year of school under my belt, so I’m no longer a freshman. But the point remains the same. I don’t believe many people reach the opportunity in their lives to simply press ‘redo’; to go back to the very same place in which they were before some seemingly fatal life decisions were made, and to get the choice to act again. And this seems to be where I find myself now.

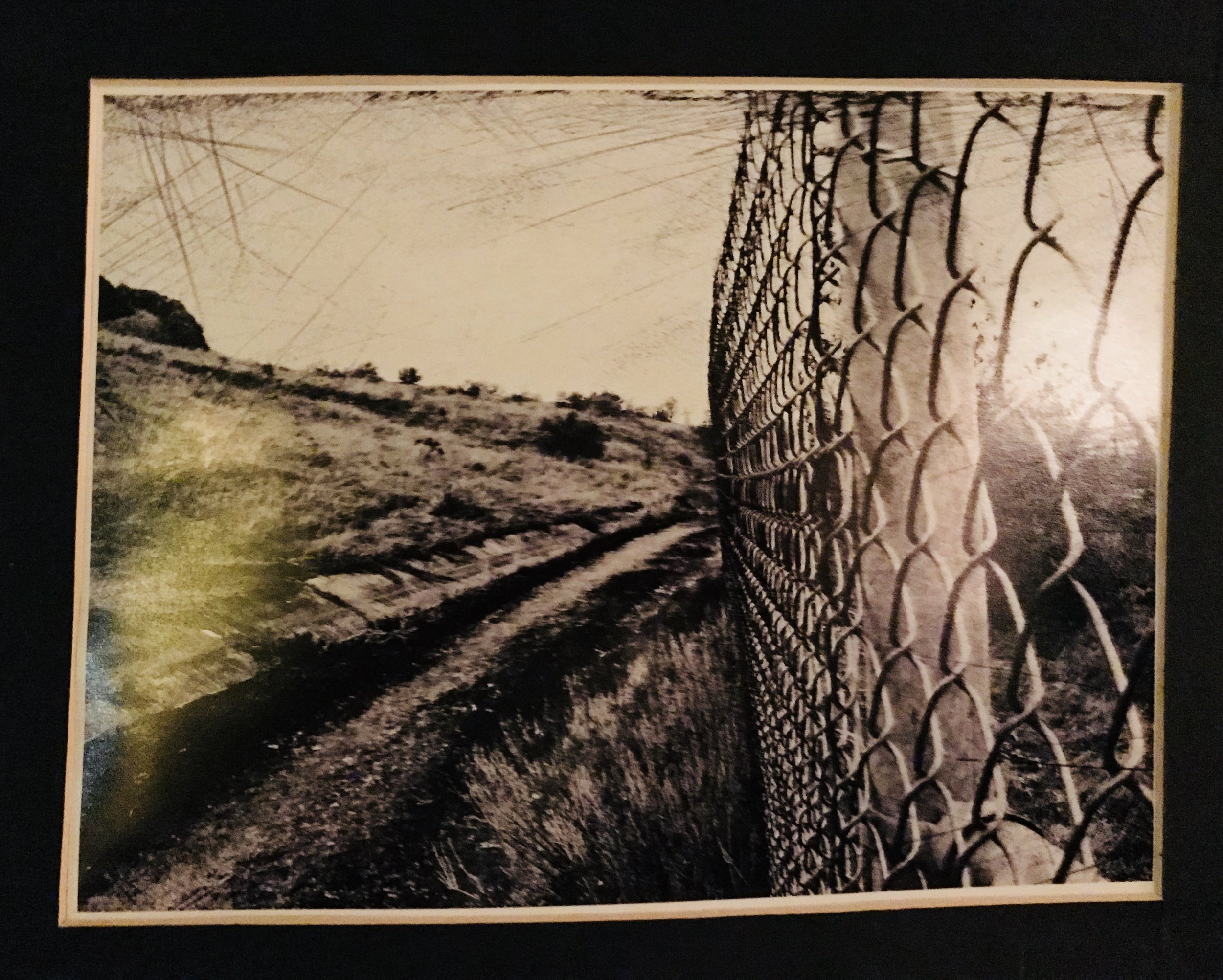

It could also be that I misunderstand the situation, and perhaps this is what it’s like to fully step into your life again - perhaps many women come to this crossroads, where they come face-to-face with the same situation where they would have acted differently years ago. And that’s the thing about incarceration, when it’s done as it’s meant to be - people just come out different. We come into the same lives we used to inhabit, but now we wear a different skin. And that’s why sometimes, there’s no better adjective to describe this whole thing than simply being weird. It’s dichotomous. You - me - I’m split in two. I experience life through multiple filters, depending on which history of mine I’m tuning into. And very specifically, it’s split in half by my time at Coffee Creek.

So, as I start this new year, in the wonderful position I have, I get to see it through this lens. I get to see it as the culmination of the work I’ve done in prison, and as the second chance I believe every human being deserves. It’s only when we put ourselves back where we first started that we are able to see just how much we’ve grown.

And how beautiful an opportunity that is.

And, if I can say so at this point, thank you for reading any part of my story that you have. Hopefully it grants a little bit of insight into the fragmented nature of change, and of our justice system. I know my life has shifted tremendously from it, and I only look forward to seeing how this develops.

I’ll see you on the other side, my friend.

The writer underwent two years at Coffee Creek Correctional Facility in Oregon, convicted for charges directly related to an active drug addiction.